|

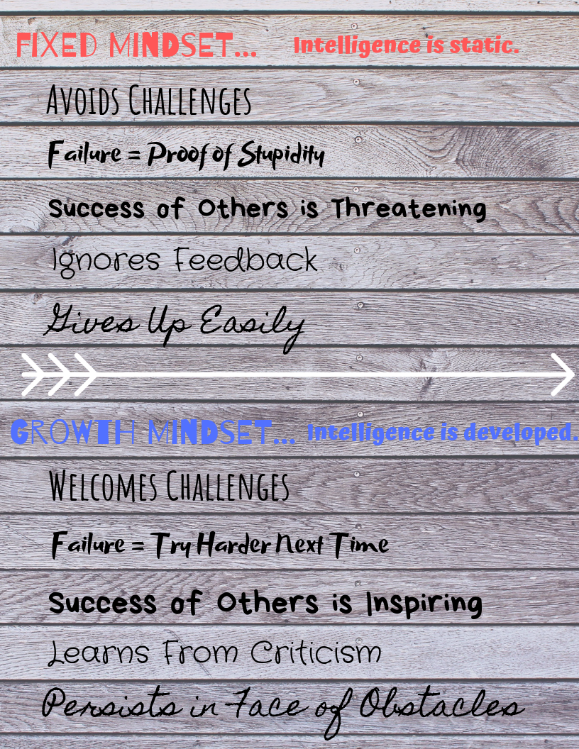

A teacher’s role is so often viewed as teaching the factual information students need to know. What is often forgotten is that teachers also need to be teaching students the skills to think and learn on their own. In order to do this, teachers need to understand students on a personal level. How is learning happening? What is affecting my students’ learning? How do I better engage them in learning? The first 8 of the “Top 20 Principles from Psychology for Prek-12 Teaching and Learning” (APA, 2015) aim to answer just those questions. Over the next few weeks we will be dissecting a couple principles at a time to help teachers better understand the principles, offer advice for current educators and include some extra resources that may be of use. Without further ado…. Principle 1 – Students’ beliefs or perceptions about intelligence and ability affect their cognitive functioning and learning (American Psychological Association, 2015). Students typically employ one of two beliefs about themselves in regards to their successes and their failures. These beliefs can impact both their learning and cognition. Students who tend to believe their performance is based on their ability generally have what is called a “fixed mindset.” These students often shy away from taking on more difficult tasks as they are afraid of failing. They take criticism personally and when they fail, feel as though it is due to their lack of intelligence. On the flip side, students who have what is called a “growth mindset” are much more flexible, successful and enjoy taking on harder tasks to see how much they have learned. These students view their successes and their failures in terms of effort – if they fail it is because they did not try hard enough, not because they aren’t smart. This type of student welcomes constructive criticism more openly - it is a suggestion to do better next time, not a personal attack. Here’s a handy chart you are more than welcome to use for yourself or your classroom that outlines the differences between the two types of mindsets: The next question is, what are the implications of this in the classroom? Often times teachers offer praise after a success in the classroom – “Wow, Tommy, you’re so smart!” Sometimes they may try to increase the self-esteem of lower-performing students by praising them when they answer very easy problems correctly. While both of these examples may seem like positive classroom practices, it actually can be very detrimental to the students involved. If teachers are constantly praising students for being smart, it is (perhaps inadvertently) encouraging students to employ a fixed mindset – success is based on intelligence. This is the opposite of what needs to happen. This doesn’t mean that teachers cannot praise their students – students still need encouragement and reassurance. However, teachers need to be careful and aware of their verbiage. A better approach would be to praise students based on their effort – “Wow, Tommy, you really worked hard on those math problems!” Or for those lower performing students who know they are behind or struggling – “Look how much you’ve improved from last week!” These types of phrases help students realize that with increased effort or by trying different strategies, outcomes can improve. This, in the long run, should foster a respect for the learning process and can help students find the motivation and perseverance to take on more difficult tasks. Additional Resources: Developing a Growth Mindset with Carol Dweck https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hiiEeMN7vbQ&feature=youtu.be Effective Effort Rubric https://s3-us-west-1.amazonaws.com/mindset-net-site/FileCenter/3JIQAYABR8M8GHQCQ05Q.pdf Growth Mindset: Clearing Up Some Common Confusions https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/42769/growth-mindset-clearing-up-some-common-confusions Free Printable Growth Mindset Posters for the Classroom https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/FREE-Growth-Mindset-Posters-for-the-Classroom-or-Bulletin-Board-3080287 Principle 2 – What students already know affects their learning. Students bring their own set of baggage into the classroom. Their past experiences with other teachers, their parents, social groups, etc. all have had an impact on them and their learning. This “baggage” determines how they will respond to new information and how they will incorporate the information into what they already know. There are two main routes to learning:

The first is pretty cut and dry. Conceptual growth is just teaching students new information. For example, students might know the moon is the moon but that is about it. Teachers can give a lesson on moon phases and move on. However, conceptual change can prove to be much more difficult. For example, a student might think the moon increases and decreases in size throughout the month. It will be more difficult to confront these misconceptions than to simply teach students about the moon’s phases. So, how do teachers know what their students already know and how should teachers address misconceptions? At the beginning of the school year or prior to the introduction of a new unit, teachers can give their students what is known as a “formative assessment.” In simple terms – a pre-test. This will allow teachers to gain a sense of what the student already knows as well as any misconceptions they may have about the topic. This can be a quick and effective way to get a baseline of students’ knowledge. When the pre-test shows that students do not have previous knowledge or misconceptions about a topic or lesson, teachers can simply go about lessons “as usual”. Hands-on activities, application activities, and reading/defining new terms are good starting points. When the pre-test shows that students might have misconceptions, a different approach is often necessary. Simply telling students what they know is wrong is not helpful and students often become resistant to any new learning or change. It is essential for students to be involved in the discovery process. If they can actively see their existing knowledge being disproved, they will a) remember the correct information longer and b) understand why their original thinking was incorrect. This can be done by having students predict answers and then assist them in doing more research to lead them to the correct answer. Another useful strategy is to ask students to explain their thought process. Often, they will realize the error in their thinking on their own. Additional Resources Teaching for Conceptual Change: Confronting Children’s Experience http://www.msuurbanstem.org/teamone/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/teachingforconceptualchange.pdf Conceptual Change: How New Ideas Take Root https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3a_4471DEU&feature=youtu.be Conceptual Change: Un-learn to Re-learn https://www.slideshare.net/jsgroff/conceptual-change-groff-14376146 Reference American Psychological Association, Coalition for Psychology in Schools and Education (2015). Top 20 principles from psychology for preK-12 teaching and learning. Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/ed/schools/cpse/top-twenty-principles.pdf Comments are closed.

|